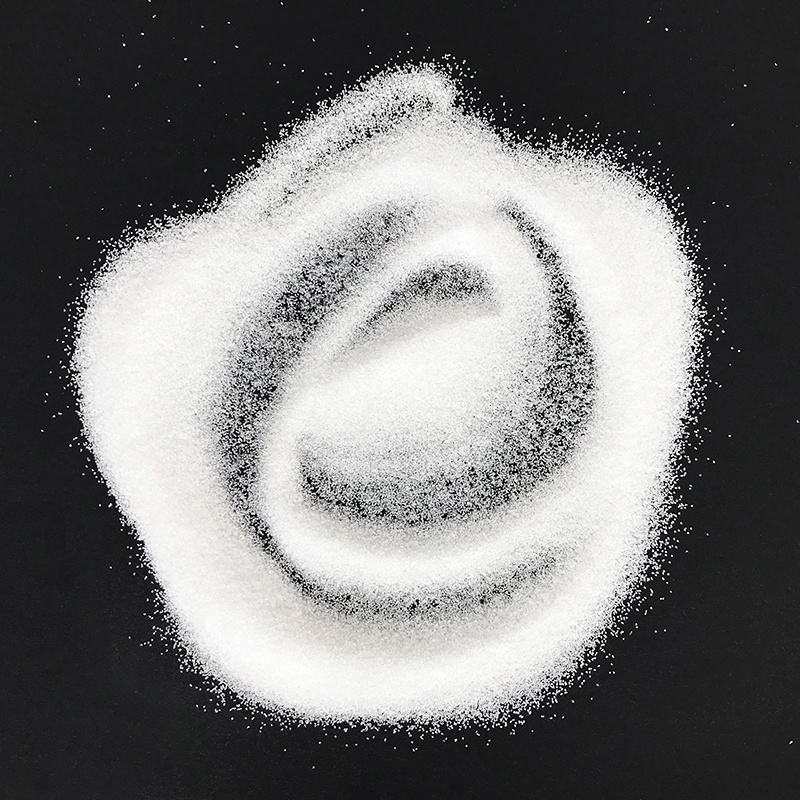

Anyone who has worked in the abrasives, refractories, or ceramics industries knows that green silicon carbide micropowder is notoriously difficult to work with. This material, with a hardness approaching that of diamond and excellent thermal and electrical conductivity, is naturally suited for precision grinding, high-grade refractories, and special ceramics. However, simply considering its hardness isn’t enough to utilize it effectively – there’s much more to this seemingly ordinary green powder than meets the eye. The key lies in “particle size.”

Experienced materials engineers often say, “When evaluating a material, first look at the powder; when evaluating the powder, first look at the particles.” This is absolutely true. The particle size of green silicon carbide micropowder directly determines whether it will be a powerful asset or a significant obstacle in downstream applications. Today, we’ll delve into how this particle size is controlled and the technical challenges involved in achieving this control.

I. “Grinding” and “Separation”: A Micron-Level “Surgical Procedure”

To obtain ideal green silicon carbide micropowder, the first step is to “break down” the large green silicon carbide crystals. This is not as simple as smashing them with a hammer, but rather a delicate process requiring extreme precision.

The mainstream method is mechanical crushing. While it sounds rough, it involves meticulous control. Ball mills are the most common “training ground,” but using ordinary steel balls can easily introduce iron impurities. More advanced methods now utilize ceramic linings and silicon carbide or zirconia grinding balls to ensure purity. Ball milling alone isn’t enough; to obtain finer and more uniform micropowder, especially in the sub-10 micrometer (µm) range, “air jet milling” is employed. This technique uses high-speed airflow to cause particles to collide and frictionally break down, resulting in minimal contamination and a relatively narrow particle size distribution. Wet grinding comes into play when ultra-fine powders (e.g., below 1 µm) are required. It effectively prevents powder agglomeration, resulting in slurries with better dispersion.

However, simply “crushing” isn’t enough; the real core technology lies in “classification.” The powders produced by crushing inevitably vary in size, and our goal is to select only the desired size range. This is like picking out only the sand particles with a diameter of 0.5 to 0.6 millimeters from a pile of sand. Dry air classification machines are currently the most widely used, utilizing centrifugal force and aerodynamics to separate coarse and fine powders with high efficiency and large output. But there’s a catch: when the powder becomes fine enough (e.g., below a few micrometers), the particles tend to clump together due to van der Waals forces (agglomeration), making it difficult for air classifiers to accurately separate them based on individual particle size. In this case, wet classification (such as centrifugal sedimentation classification) can sometimes be useful, but the process is complex and the cost increases.

So, you see, the entire particle size control process is essentially a constant struggle and compromise between “crushing” and “classification.” Crushing aims for finer particles, but too fine particles are prone to agglomeration, hindering classification; classification aims for greater precision, but often struggles with agglomerated fine powders. Engineers spend most of their time balancing these conflicting demands.

II. “Obstacles” and “Solutions”: The Thorns and the Light on the Path to Particle Size Control

Controlling the particle size of green silicon carbide micropowder reliably involves more than just crushing and classification. Several real “obstacles” stand in the way, and without addressing them, precise control is impossible.

The first obstacle is the backlash caused by “hardness.” Green silicon carbide is extremely hard, requiring enormous energy to crush, resulting in significant equipment wear. During ultra-fine grinding, the wear of grinding media and liners produces a large amount of impurities. These impurities mix into the product, compromising its purity. All your hard work controlling particle size becomes pointless if the impurity levels are too high. Currently, the industry is desperately developing more wear-resistant grinding media and liner materials, and improving equipment structures, all to grapple with this “tough tiger.”

The second tiger is the “law of attraction” in the world of fine powders – agglomeration. The finer the particles, the larger the specific surface area, and the higher the surface energy; they naturally tend to “clump together.” This agglomeration can be “soft agglomeration” (held together by intermolecular forces, such as van der Waals forces, which are relatively easy to break apart), or the more formidable “hard agglomeration” (where during crushing or calcination, the particle surfaces partially melt or undergo chemical reactions, welding them together tightly). Once agglomerates form, they masquerade as “large particles” in particle size analysis instruments, seriously misleading your judgment; in practical applications, such as in polishing liquids, these agglomerates are the “culprits” that scratch the workpiece surface. Solving agglomeration is a global challenge. Besides adding additives and optimizing the process during crushing, a more powerful approach is to modify the powder surface, giving it a “coating” to reduce surface energy and prevent it from constantly wanting to “clump together.”

Ⅲ.The third tiger is the inherent uncertainty in “measurement.”

How do you know that the particle size you’ve controlled is what you think it is? Particle size analyzers are our eyes, but different measurement principles (laser diffraction, sedimentation, image analysis), and even different sample dispersion methods under the same principle, can yield significantly different results. This is especially true for powders that have already agglomerated; if proper dispersion isn’t achieved before measurement (e.g., adding dispersants, ultrasonic treatment), the data obtained will be far from the actual situation. Without reliable measurement, precise control is just empty talk.

Despite these challenges, the industry is constantly seeking solutions. For example, the refinement and intelligence of the entire process is a major trend. Through online particle size monitoring equipment, real-time data feedback and automatic adjustment of crushing and classification parameters lead to a more stable process. Furthermore, surface modification technology is receiving increasing attention, no longer a “remedy” after the fact, but integrated into the entire preparation process, suppressing agglomeration from the source and improving the dispersibility of the powder and its compatibility with the application system. III. The Call of Applications: How Does Particle Size Become the “Philosopher’s Stone”?

Why go to such great lengths to control particle size? Looking at practical applications makes it clear. In the field of precision grinding and polishing, such as polishing sapphire screens and silicon wafers, the particle size distribution of green silicon carbide micro-powder is a “lifeline.” It requires an extremely narrow and uniform particle size distribution, absolutely free of “oversized particles” (also called “abrasive particles” or “killer particles”), otherwise a single deep scratch can ruin the entire expensive workpiece. At the same time, the powder must not have hard agglomerates, otherwise the polishing efficiency will be low, and the surface finish will not be satisfactory. Here, particle size control is rigorously maintained at the nanoscale.

In advanced refractory materials, such as ceramic kiln furniture and high-temperature furnace linings, particle size control focuses on “particle size distribution.” Coarse and fine particles are mixed in a certain proportion; coarse particles form the framework, and fine particles fill the gaps. This allows for dense and strong sintering at high temperatures, resulting in good thermal shock resistance. If the particle size distribution is unreasonable, the material will either be porous and not durable, or too brittle and prone to cracking. In the field of special ceramics, such as bulletproof ceramics and wear-resistant sealing rings, the powder particle size directly affects the microstructure and final performance after sintering. Ultrafine and uniform powders have high sintering activity, allowing for higher density and finer grain ceramics at lower temperatures, thus significantly improving their strength and toughness. Here, particle size is the intrinsic secret to “strengthening” the ceramic material.