Have you ever tried touching a piece of etched glass? The delicate frosted texture is like having the morning mist frozen on your fingertips. In our industry, if we’re talking about who can “dress up” glass with the most charm, white fused alumina sandblasting is definitely a master. Today, I’ll talk about this seemingly ordinary yet special process in the field of glass etching.

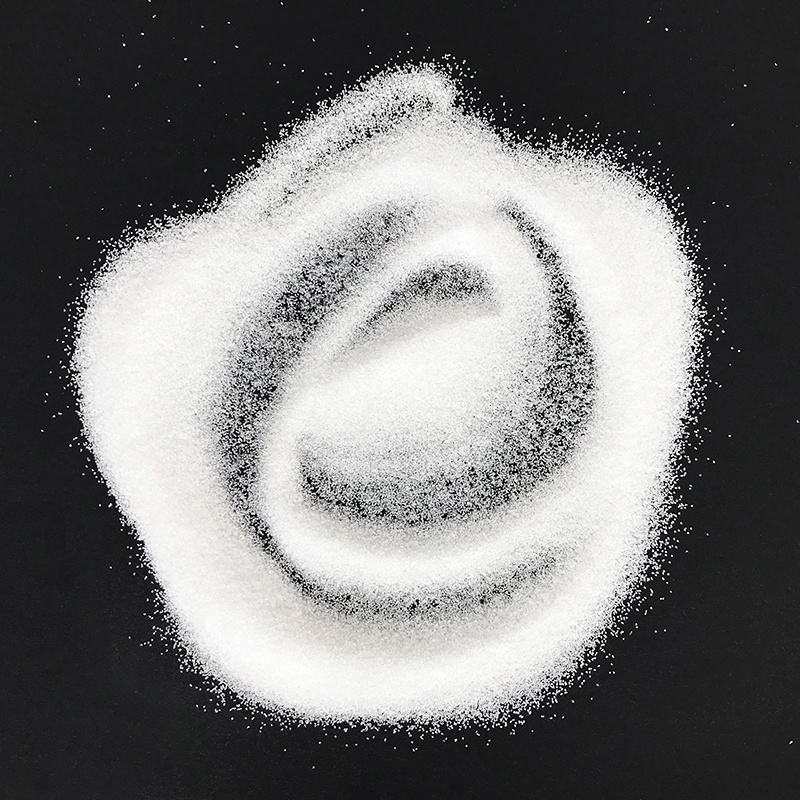

First Encounter with White Fused Alumina: The Unassuming “Little Diamond”

Ten years ago, I first encountered white fused alumina sandblasting. My mentor pointed to the bag of seemingly ordinary white granules and said, “Don’t be fooled by its unassuming appearance; this is the ‘needle’ for glass etching.” Later, I learned that white fused alumina is a crystalline form of alumina, with a Mohs hardness of 9, second only to diamond. But its uniqueness lies in the balance between hardness and toughness—hard enough to scratch glass, yet not so sharp as to damage the substrate. The preparation of this material is also quite interesting. Bauxite, smelted at over 2000 degrees Celsius in an electric arc furnace, slowly crystallizes into these white particles. Each particle resembles a tiny polyhedron; under a microscope, its edges are distinct yet not overly sharp. It is this physical property that makes it an ideal medium for glass etching.

The “Magic Moment” in the Sandblasting Workshop

Entering the sandblasting workshop, the initial sound resembles a continuous gust of wind, but upon closer listening, it’s interspersed with a fine “shh” sound, like silkworms eating leaves. Operator Lao Li, wearing a protective mask, holds a spray gun and moves it slowly across the glass surface. Through the observation window, you can see the white sand flowing from the nozzle, striking the transparent glass, instantly softening and blurring its surface. “Hands must be steady, movements must be even,” Lao Li often repeats. The distance between the spray gun and the glass, the speed of movement, and subtle changes in angle all affect the final result. Too close or too long, and the glass will be over-etched, even developing uneven marks; too far, and the effect will be indistinct and lack depth. This craft remains largely irreplaceable by machines because it requires a “feel” for the material’s properties.

The Uniqueness of White Fused Alumina: Why It?

You might ask, with so many sandblasting materials available, why is white fused alumina so favored in glass etching? First, its hardness is just right. Softer materials, like silica sand, are too inefficient and easily generate dust pollution; harder materials, like silicon carbide, can easily over-erode the glass surface, even creating micro-cracks. White fused alumina is like a precise sculptor, effectively removing material from the glass surface without damaging its structure. Second, the shape and size of white fused alumina particles can be controlled. Through a sieving process, products with different particle sizes from coarse to fine can be obtained. Coarse particles are used for rapid material removal, creating a rough frosted effect; fine particles are used for fine polishing or creating a soft matte effect. This flexibility is unmatched by many other sandblasting materials. Furthermore, white fused alumina is chemically stable, does not react with glass, and does not leave contaminants on the surface. Sandblasted glass requires only simple cleaning, which is especially important in mass production.

From Mass Production to Artistic Creation

The industrial application of white fused alumina sandblasting is already commonplace. Patterns on bathroom glass doors, logos on wine bottles, and decorative designs on building facades are all products of sandblasting. But you may not know that this technology is quietly entering the art world. Last year, I visited a modern glass art exhibition. One piece impressed me deeply: an entire glass wall, treated with sandblasting of varying intensities, created a gradient effect reminiscent of a landscape painting. From afar, it appeared as hazy distant mountains; only upon closer inspection could one discover the subtle layers of light and shadow. The artist told me that he experimented with various sandblasting materials and ultimately chose white fused alumina because it offered the finest control over grayscale. “Each grain of white fused alumina striking the glass is like an extremely fine ink dot,” he described. “Thousands upon thousands of these ‘ink dots’ make up the entire picture.”

Craftsmanship Details: Seemingly Simple, Yet Exquisitely Intricate

The operation of white fused alumina sandblasting may seem simple, but it actually involves many intricacies. The first is the control of air pressure. The pressure is typically maintained within the range of 4-7 kgf/cm². Too little pressure results in insufficient impact from the abrasive particles; too much pressure can damage the glass surface. This pressure range is the “golden zone” discovered through generations of practical experience. Secondly, there’s the sandblasting distance. Generally, a nozzle distance of 15-30 cm from the glass surface yields the best results. However, this distance needs to be adjusted flexibly based on the glass thickness, required etching depth, and pattern complexity. Experienced craftsmen can judge the appropriate distance by sound and visual inspection. Then there’s the recycling of abrasive particles. High-quality white fused alumina can be reused 5-8 times, but with increased use, the particles gradually become rounded, reducing cutting efficiency. At this point, new alumina needs to be added or the entire batch replaced. Judging the “fatigue” of the abrasive particles relies on experience—observing changes in the sandblasting effect and feeling the difference in the feel during operation.

Problems and Solutions: Wisdom in Practice

Any process encounters problems, and white fused alumina sandblasting is no exception. The most common problem is blurred pattern edges. This is usually caused by a loose fit between the sandblasting template and the glass, allowing abrasive particles to penetrate through the gaps. The solution seems simple—just press the template tighter—but in reality, the choice of tape and the technique of application are crucial. Xiao Wang in our workshop invented a double-layer application method: first, use soft tape as a buffer layer, then fix it with high-strength tape, greatly reducing the problem of sand seepage at the edges. Another issue is uneven surface. This could be due to uneven spray gun movement or inconsistent abrasive grain moisture. Although white fused alumina is chemically stable, if improperly stored and exposed to moisture, the particles will clump together, affecting the uniformity of sandblasting. Our current approach is to install a small drying device at the sandblasting machine inlet to ensure uniform abrasive grain drying.

Future Possibilities: The Rebirth of Traditional Processes

With technological advancements, white fused alumina sandblasting is constantly innovating. The advent of CNC sandblasting machines has made large-scale production of complex patterns possible; the development of new template materials allows for more intricate patterns. However, I believe the most interesting direction for this process is its integration with digital technology. Some studios have begun experimenting with directly converting digital images into sandblasting parameters, controlling the spray gun’s movement trajectory and sandblasting intensity through programming to “print” images with continuous tones on glass. This retains the unique texture of sandblasting while overcoming the technical limitations of traditional templates. However, no matter how advanced the technology, the agility of manual operation and the intuitive judgment to adjust to the material’s condition in real time are still difficult for machines to completely replace. Perhaps the future direction is not machines replacing humans, but human-machine collaboration—machines handling repetitive tasks, while humans focus on creativity and key steps.