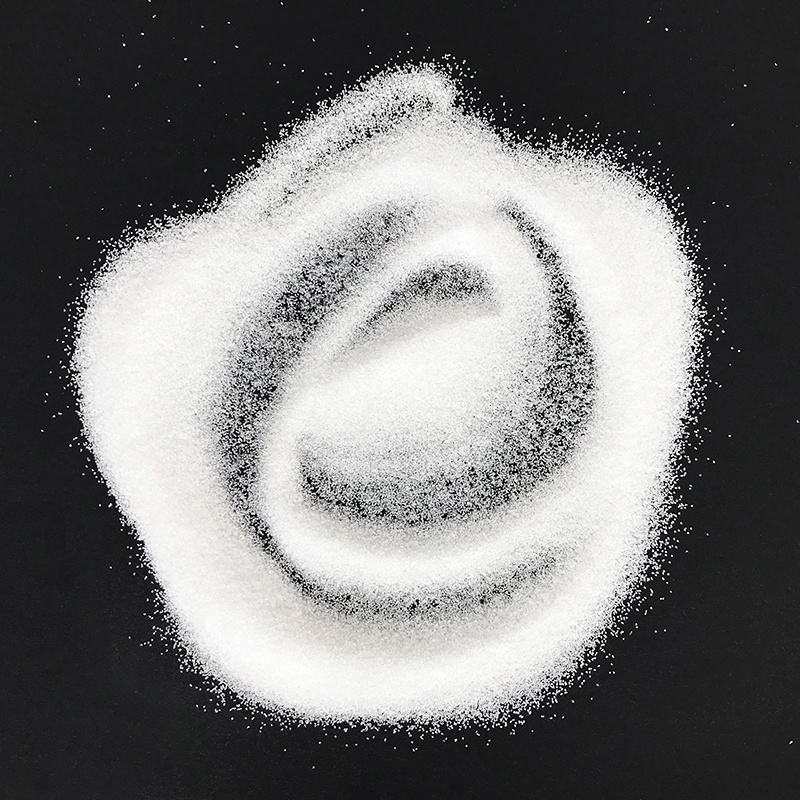

A few days ago, I was chatting with a friend over tea, and he jokingly said, “The alumina you guys are researching all the time, isn’t it just the raw material for ceramic cups and sandpaper?” This left me speechless. Indeed, in the eyes of ordinary people, alumina powder is just an industrial material, but in our biomedical engineering circle, it’s a hidden “multitasker.” Today, let’s talk about how this seemingly ordinary white powder has quietly infiltrated the field of life sciences.

I. Starting from the Orthopedic Clinic

What impressed me most was the orthopedic conference I attended last year. An old professor presented fifteen years of follow-up data on alumina ceramic artificial joint replacements—with a survival rate exceeding 95%, which amazed all the young doctors present. Why choose alumina? There’s a lot of science behind it. First, its hardness is high enough, and its wear resistance is much stronger than traditional metal materials. Our human joints endure thousands of frictions every day. Traditional metal-on-plastic prostheses will produce wear debris over time, causing inflammation and bone resorption. However, the wear rate of alumina ceramics is only one percent of that of traditional materials, a revolutionary figure in clinical practice.

Even better is its biocompatibility. Our laboratory has conducted cell culture experiments and found that osteoblasts attach and proliferate better on the surface of alumina than on some metal surfaces. This explains why, clinically, alumina prostheses bond particularly strongly with bone. However, it’s important to note that not just any alumina powder can be used. Medical-grade alumina requires a purity of over 99.9%, with crystal grain size controlled at the micron level, and it must undergo a special sintering process. It’s like cooking—ordinary salt and sea salt can both season food, but high-end restaurants choose salt from specific origins.

II. The “Invisible Guardian” in Dentistry

If you’ve been to a modern dental clinic, you’ve likely already encountered alumina. Many of the popular all-ceramic crowns are made from alumina ceramic powder. Traditional metal-ceramic crowns have two problems: first, the metal affects aesthetics, and the gum line is prone to turning blue; second, some people are allergic to metal. Alumina all-ceramic crowns solve these problems. Its translucency is very similar to natural teeth, and the resulting restorations are so natural that even dentists have to look closely to tell the difference. A senior dental technician I know used a very apt analogy: “Alumina ceramic powder is like dough—it’s highly malleable and can be molded into various shapes; but after sintering, it becomes as hard as a stone, strong enough to crack walnuts (though we don’t recommend actually doing that).” Even more popular in recent years are 3D-printed alumina crowns. Through digital scanning and design, they are directly printed using alumina slurry, achieving an accuracy of tens of micrometers. Patients can come in the morning and leave with their crowns in the evening—something unimaginable ten years ago.

III. “Precise Navigation” in Drug Delivery Systems

Research in this field is particularly interesting. Because alumina powder has many active sites on its surface, it can adsorb drug molecules like a magnet and then release them slowly. Our team has conducted experiments using porous alumina microspheres loaded with anticancer drugs. The drug concentration at the tumor site was 3-5 times higher than with traditional drug delivery methods, while systemic side effects were significantly reduced. The principle is not difficult to understand: by making alumina powder into nano- or micro-sized particles and modifying the surface, it can be linked to targeting molecules, like giving the drug a “GPS navigation” system to go directly to the lesion. Moreover, alumina eventually decomposes into aluminum ions in the body, which can be metabolized by the body at normal doses and will not accumulate long-term. A colleague who studies targeted therapy for liver cancer told me that they used alumina nanoparticles to deliver chemotherapy drugs, increasing the tumor inhibition rate by 40% in a mouse model. “The key is to control the particle size; 100-200 nanometers is ideal—too small and they are easily cleared by the kidneys, too large and they can’t enter the tumor tissue.” This kind of detail is the essence of the research.

IV. “Sensitive Probes” in Biosensors

Alumina is also playing a significant role in early disease diagnosis. Its surface can be easily modified with various biomolecules, such as antibodies, enzymes, and DNA probes, to create highly sensitive biosensors. For example, some blood glucose meters now use alumina-based sensor chips. Glucose in the blood reacts with enzymes on the chip to produce an electrical signal, and the alumina layer amplifies this signal, making the detection more accurate. Traditional test strip methods may have a 15% error rate, while alumina sensors can keep the error within 5%, a significant difference for diabetic patients. Even more cutting-edge are sensors that detect cancer biomarkers. Last year, an article in the journal *Biomaterials* showed that using alumina nanowire arrays to detect prostate-specific antigen resulted in a sensitivity two orders of magnitude higher than conventional methods, meaning it may be possible to detect signs of cancer at a much earlier stage.

V. “Scaffolding Support” in Tissue Engineering

Tissue engineering is a hot topic in biomedicine. Simply put, it involves cultivating living tissue in vitro and then transplanting it into the body. One of the biggest challenges is the scaffold material – it must provide support for the cells without causing toxic side effects. Porous alumina scaffolds have found their niche here. By controlling the process conditions, it’s possible to create alumina sponge-like structures with a porosity exceeding 80%, with pore sizes just right for cells to grow into, allowing nutrients to flow freely. Our laboratory tried using alumina scaffolds to cultivate bone tissue, and the results were unexpectedly good. Osteoblasts not only survived well but also secreted more bone matrix. Analysis revealed that the slight roughness of the alumina surface actually promoted cell function expression, which was a pleasant surprise.

VI. Challenges and Prospects

Of course, the application of alumina in the medical field is not without its challenges. First, there’s the cost issue; the preparation process for medical-grade alumina is complex, making it dozens of times more expensive than industrial-grade alumina. Second, long-term safety data is still being accumulated. Although the current outlook is optimistic, scientific rigor requires continuous monitoring. In addition, the biological effects of nano-alumina need further in-depth research. Nanomaterials have unique properties, and whether these are beneficial or harmful depends on solid experimental data. However, the prospects are bright. Some teams are now researching intelligent alumina materials – for example, carriers that release drugs only at specific pH values or under the action of enzymes, or bone repair materials that release growth factors in response to stress changes. Breakthroughs in these areas will revolutionize treatment methods.

After hearing all this, my friend remarked, “I never imagined there was so much to this white powder.” Indeed, the beauty of science is often hidden in the ordinary. The journey of alumina powder from industrial workshops to operating rooms and laboratories perfectly illustrates the charm of interdisciplinary research. Materials scientists, doctors, and biologists are working together to breathe new life into a traditional material. This interdisciplinary collaboration is precisely what drives progress in modern medicine.

So the next time you see an aluminum oxide product, consider this: it might not just be a ceramic bowl or a grinding wheel; it could be quietly improving people’s health and lives in some form, in a laboratory or hospital somewhere. Medical progress often happens this way: not through dramatic breakthroughs, but more often through materials like aluminum oxide, gradually finding new applications and silently solving practical problems. What we need to do is maintain curiosity and an open mind, and discover extraordinary possibilities in the ordinary.