Yesterday, Zhang from the lab complained to me again that the abrasive sample test data was always inconsistent. I patted him on the shoulder and said, “Brother, as materials scientists, we can’t just look at data sheets; we have to get our hands dirty and understand the characteristics of these white fused alumina micropowders.” This is true; just like an experienced chef knows the right temperature for cooking, we testers need to “befriend” these seemingly ordinary white powders first.

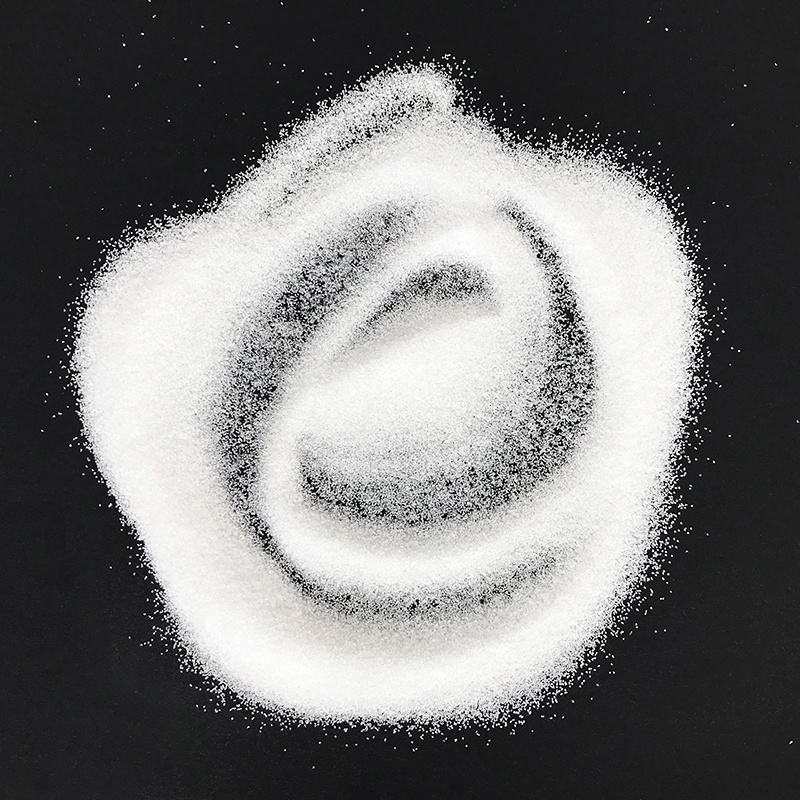

White fused alumina micropowder is known in the industry as a crystalline form of aluminum oxide, with a Mohs hardness of 9, second only to diamond. But you’d be wrong to treat it as just another hard material. Last month, we received three batches of samples from different manufacturers. They all looked like snow-white powder, but under an electron microscope, they each had their own characteristics—some particles had sharp edges like broken glass shards, while others were as smooth as fine beach sand. This leads to the first problem: hardness testing isn’t a simple numbers game.

We commonly use a microhardness tester, where you press the indenter down and the data comes out. But there are nuances: if the loading speed is too fast, brittle particles might suddenly crack; if the load is too light, you won’t measure the true hardness. Once, I deliberately tested the same sample at two different rates, and the results differed by a full 0.8 Mohs hardness units. It’s like tapping a watermelon with your knuckles; too much force and you crack it, too little and you can’t tell if it’s ripe. So now, before testing, we have to “condition” the samples in a constant temperature and humidity environment for 24 hours to let them adapt to the lab’s “temperament.”

As for wear resistance testing, that’s even more of a skilled craft. The conventional method is to use a standard rubber wheel to rub the sample under a fixed pressure and measure the wear. But in practice, I found that every 10% increase in environmental humidity could cause a fluctuation of more than 5% in the wear rate. Last year during the rainy season, a set of experiments repeated five times showed wildly scattered data, and we finally discovered it was because the air conditioner’s dehumidification wasn’t working properly. My supervisor said something that I still remember: “The weather outside the lab window is also part of the experimental parameters.”

Even more interesting is the influence of particle shape. Those sharply angled micro-particles wear down faster under low loads—like a sharp but brittle knife that chips easily when cutting hard materials. Spherical particles, specially shaped through a specific process, exhibit astonishing stability under long-term cyclic loading. This reminds me of the pebbles on the riverbed near my hometown; years of flood erosion only made them stronger. Sometimes, absolute hardness is no match for appropriate toughness.

There’s another easily overlooked point in the testing process: particle size distribution. Everyone focuses on the average particle size, but what truly affects wear resistance is often that 10% of ultra-fine and coarse particles. They’re like the “special members” of a team; too few and they have no effect, too many and they disrupt overall performance. Once, after we screened out 5% of the ultra-fine powder, the wear resistance of the entire batch of material improved by 30%. This discovery earned me praise from Old Wang for half a month at the team meeting.

Now, after every test, I’ve developed a habit of collecting the discarded samples. The white powders from different batches actually have slightly different lusters under the light; some are bluish, some yellowish. The experienced technicians say this is a manifestation of differences in crystal structure, and these differences are often only noted as a small footnote on the instrument data sheet. Those who work with their hands know that materials have a life of their own; they tell their stories through subtle changes.

Ultimately, testing white corundum micro-powder is like getting to know a person. The numbers on the resume (hardness, particle size, purity) are just basic information; to truly understand it, you need to see its performance under different pressures (load changes), in different environments (temperature and humidity changes), and after prolonged use (fatigue testing). The million-dollar wear testing machine in the lab is very precise, but the final judgment still relies on the experience of a touch and a glance—just like an old machinist who can tell what’s wrong with a machine just by listening to its sound.

Next time you see a simple “Hardness 9, Excellent Wear Resistance” on a test report, you might want to ask: under what conditions, in whose hands, and after how many failures was this “excellent” result achieved? After all, those quiet white powders don’t speak, but every scratch they leave behind is the most honest language.